1.2.2 ‘Standard English’: Beliefs

Concept: Monolithic concepts of English have developed for both social and cognitive reasons

The popular view of English as a monolithic system has developed largely as a result of two factors, one cognitive and one social:

- our generally unconscious use of language, and our inability to observe its development, storage and processing in the mind (Hall, 2005)

- the association between ‘Standard English’ and nationalism, fostered by the education system and other institutions, and the consequent doctrine of correctness (Armstrong and Mackenzie, 2013)

Such factors have led to a set of ‘folk beliefs’ which are very different from the perspective offered by linguistics.

Activity

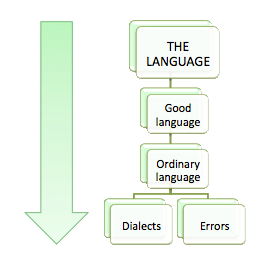

Look at Figures 1.4 and 1.5 which, adapting work by (Preston, 2002), depict folk and linguistic views of language.

Figure 1.4: A ‘folk view’ of what language is

Figure 1.5: A linguistic view of what language is

- How do you understand these two diagrams? What do you think the labels in the boxes refer to in each case? Can you say how the different levels of concepts in the diagrams relate to each other?

- With which concept would you associate ‘Standard English’ in each diagram?

- Where do you see non-native users of English being placed in these diagrams?

Feedback

According to the 'folk' view:

- 'THE LANGUAGE' is an ideal, abstract system, existing outside of particular communities and individual minds. 'Good language' is what is considered correct usage of the abstract system of 'THE LANGUAGE'. 'Ordinary language' is the way most users use 'THE LANGUAGE', and comes in two forms: acceptable but more or less pleasing 'dialects' (depending on region and often viewed as quaint, comic, ugly, etc.) and unacceptable 'errors' (normally in writing, where 'good language' is expected).

- 'Standard English' is, essentially, 'THE LANGUAGE', which 'good language' adheres to and 'ordinary language' often departs from.

- The arrow represents decreasing 'correctness' or some other normative value (e.g. 'politeness' or 'formality').

- Non-native speakers are often assumed to lack proficiency, and their usage is therefore associated strongly with 'errors' (which teachers correct). The minority of 'successful' non-native speakers are assumed to use 'good language', and not their own, or native speakers' 'dialects'.

According to the linguistic view:

- 'THE LANGUAGE' is a social construction, an abstraction from the dynamic and highly variable nature of idiolects and dialects, and defined in terms of common structure and mutual intelligibility. 'Dialects' can be understood here as the commonalities in language structure and use of distinct groups of speakers who are usually defined in terms of region and socioeconomic status. 'Idiolects' can be understood as the language forms and uses of individual users.

- 'Standard English' is one of the dialects—which just happens to be codified, institutionalised, used in writing, spoken with a prestigious non-localised accent, etc. (In the actual practice of linguistics, this belief is hard to sustain, and many argue that it has led to significant distortions in supposedly 'objective' description and analysis: see (Armstrong and Mackenzie, 2013).

- The arrow represents abstractness, going from the neuropsychological level (of individuals' minds/brains), through the sociocultural level (social groups), and ultimately to idealisation.

- Non-native speakers have typically been ignored in linguistics.

Discussion point 1.2

The word dialect is often used outside linguistics to refer to language varieties that are not viewed as having the status of ‘full languages’. It is used in China, for example, for the hundreds of regional languages which are written with the same system of characters but which may be mutually unintelligible with Mandarin. It’s commonly used in Mexico to refer to indigenous languages. Is there anything similar in your country or other countries you’re familiar with? What do you feel about the linguistic claim that ‘Standard English’ is (just) a non-regional dialect? Share your thoughts in the discussion section at the bottom of the page.

Although popular beliefs about language should not be underestimated, they don’t reflect observable reality very accurately (and can often lead to social injustices). So although people have monolithic beliefs about English, the actual forms and uses of English continue to be plurilithic, even in the heartlands of ‘Standard English’. Even after over a century of mass schooling and mass exposure to ‘good language’ through radio and subsequently TV, ‘the language’ won’t stay still.

This is especially so with globalisation. Indeed, (Pennycook, 2007, 2009) coined the term plurilithic as part of a critical analysis of the cultural politics of national language institutionalisation in our increasingly hybrid and globalised world. But what does it mean for English language teaching (ELT)?

Interesting regarding indigenous languages being classed as a dialect and not a language. Shows the need for decolonising our thinking when discussing ‘standard English’.

‘Standard English’ as a non-regional dialect challenges language prestige, elitism, and linguistic imperialism, which could further lead to cultural imperialism.

I agree – we definitely need to decolonise the way we talk about languages and language communities around the world, especially as calling Indigenous languages dialects, rather than affording them the same status as a majority language, is a fairly common practice, not just in Mexico, but elsewhere as well.

Despite the fact that North and South Saami in many ways are not mutually intelligible, they are often referred to as dialects anyway by Swedish and Norwegian authorities alike. Most Saami languages are treated as variants of a single Saami language, despite the fact that if the same logic were to be applied to Nordic languages, we would have to think of Swedish, Danish and Norwegian as dialects of an unnamed pan-Nordic language.

Comment *I am Colombian and I am proud of the rich linguistic diversity of my country. In different regions of Colombia indigenous languages are spoken, which in my opinion are not dialects since they are independent from Spanish and have their own grammatical structures, vocabularies and unique worldviews. According to official data, Colombia has 65 indigenous languages, each with its own history and cultural value.

In addition to these indigenous languages, Colombia also has dialectal varieties of Spanish, which are distinguished by their phonetic, lexical and morphosyntactic characteristics. These varieties have emerged from the mixture of cultures and history that has enriched the country. I believe that it is important to recognize and value both the indigenous languages and the dialectal varieties of Spanish and other languages worldwide. A single dialect should not be considered as something standard, but rather it should be recognized that there are different dialects and that each one has its own particularities within the language. The most important thing is that there is effective communication.

In the UK there are many people who would hold the view that standard English is the more upper-class form of English, which I would typically associate with varieties of English features such as high register and jargon within their speech, on the other hand, there is non-standard English, which is more colloquial language, users who use non-standard English who I associate with this variety of English are those from the lower class such as those from Council house estate areas.

I feel that standard is almost like a dialect in its on way, while non-standard English users’ repertoires are more limited to non-codified, simplistic words which don’t appear in dictionaries, use more low register, and almost never omit Jargon, or specialist terminology, but in comparison to standard English users, the two varieties are both mututally intelligble but different in some ways.

The ability to write & speak standardized English is still used as a measure of your intelligence & capability in America. But let’s be clear, “American English” is a dialect of British English. In addition to America’s regional dialects (southern /midwestern/northern etc..) there are “sub-regional dialects; for example; the “Creole” of the Gullah Geechee in South Carolina. And the “Yat Slang” in New Orleans.

Dialects provide important insights into unique cultures and historical experiences of a particular group of people. For example, it was illegal for Black Americans to learn to read or write & the offense was punishable by death during American Chattel slavery. Nowadays Black American sub-culture & dialects are vilified & yet appropriated for profit by everyone from influencers & advertising companies to music & entertainment globally. In my opinion, It’s a matter of control & power.

I completely agree with everything you have said! I am in an American classroom right now, we are discussing what is Standard English as part of our MATESOL class. Some of my white and American classmates unintentionally reveal their monolithic understandings of English which is especially funny to me as a Turkish person who learned the English language. I am literally an example of a plurilithic understanding of English. I am evidence that there are other Englishes. But, they argue against this to my face. Funnily enough, I know for a fact that they would not be able to get my 8.5 from IELTS if they took the exam themselves.

I am from Australia but I’ve been living in Germany for almost 25 years. When I first arrived here, I couldn’t speak German but I soon picked up that the people I was meeting through my German girlfriend (who later became my wife) were surprised to discover that I spoke “normal” or “proper” English. A lot has changed since then, but older generations (including German school teachers of English) have very strange notions of what constitutes “proper English”–it’s a mixture of Queen’s/King’s English and how BBC radio announcers spoke 50 years ago, along with a wish for English to be used as they imagine it must be in some idealised notion of a pretty English village in the home counties. They seem oblivious to the lingusitic diversity of the Brits. This is strange given that linguistic diversity is a prominent feature of German, whether it’s Hochdeutsch, Platt, Bayerisch, Schwiizerdütsch or the many dialects found in the rural areas left behind by the modern world. And then there’s Alemannish, something completely different from all the rest. But despite this, people who speak a “Dialekt” are considered to either be cute and worthy of protection, or simply stupid and simple.

Thinking about Standardised English: On my first visit to Germany, I was sitting in an Irish pub in Berlin with my German girlfriend and some friends of hers. A small group of Irish musicians were playing music and when they played a song about convicts being sent to Australia, I told them I was from that country. One of them said “But you don’t sound like an Aussie, mate” and so I countered with “Yeah, because I’m educated.”

Your situation is similar to mine! I’m British and have been living in Germany for 29 years, also arriving with very little knowledge of the German language. I noticed that, when I was in the company of several native-German speakers, they found it necessary to announce that they were switching to Hochdeutsch (“High German”) as there was a non-native speaker in their midst. It was a nice gesture, but as I learned German with a Schwäbische dialect by living in the Black Forest, this switch wasn’t necessary or all that helpful! They no longer do this!

Another thing I’ve noticed is that my English accent is valued here. As an English Language Teacher from Oxford, several adult students have said over the years that they always wanted a teacher with an Oxford accent. That’s all well and good, but as learners, they need to be exposed to speakers with many different accents and dialects, and I have always done this by using videos and podcasts, and the occasional classroom visitor. Some adult learners say they want to speak English “without an accent” and to “sound like a native speaker”. This always worries me as it’s only really possible when learned as a bilingual from childhood; adult learners would need to put in a great deal of work to achieve this somewhat unnecessary aim. I encourage them to improve their accuracy, but to concentrate more on fluency so they have a good working use of English. A student who had been in one of my adult classes for several years left recently, giving the reason that he can converse with anyone that he meets whether they are a native- or non-native speaker of English. His English isn’t perfect, and he knows that, but it’s accurate enough and he has fluency and the confidence to use it socially. He had achieved his language learning aims.

I am Serbian, living and teaching English in Italy. I’ve noticed two distinct situations… in the UK, the dialect would probably depend on your (apparently low) education level and where you come from, while in Italy, the educated speakers do use their regional dialect, but can also speak “standard Italian”. I am not sure if it is the same in England, so I would be glad if someone could reply

Yes, I think this is a really good point! When I was teaching English in China my students spoke Mandarin/Putonghua at school, but also local dialect among themselves and with their families (and their grandparents sometimes could only speak in dialect). So, Putonghua was a sign of their education and I suppose ambition to move beyond their local area and communicate with people in a broader geographical area. I do remember one friend saying he ‘wasn’t very good at Chinese’, which at the time I found a strange thing to say. On the other hand, my students and friends found their local dialect very fun and thought it was amusing to teach me dialect words and pronunciations. They seemed to feel more ownership and playfulness with the dialect. All this is to say that I think English operates in a similar way, between local dialects/accents and ‘Standard English’, but that we are perhaps not so explicit or upfront about it.

Being particularly familiar with Romania and Italy, I can say there certainly are tens of ‘dialects’ in these countries, and none are recognized as actual languages, as in the case of Mexico presented in the course. Wikipedia claims that Romanian dialects are all mutually intelligible, but I disagree to an extent. In my experience, you can put together a person from the south/south-east of the country with someone from the north and difficulties of understanding would arise, especially if there is a generational gap. Unfortunately, many of the regional languages of both Romania and Italy are vulnerable or seriously endangered, with older generations mostly being the ones keeping the languages alive. In Italy, these languages are so complex and have German or French influences, and one regional language I was exposed to sounded closer to Romanian than standard Italian!

I agree with the linguistic claim that Standard English is in itself a dialect…I would say it is a ‘variety’ of the language. It shouldn’t be given more importance or status than the other varieties, in a perfect world…

I’d be interested to learn more about others’ regional languages from their countries and their views on them.

I have taught English for a variety of reasons, in different countries with a variety of different needs, goals and contexts. Most of the courses I have taught have been accredited ones leading to exams or internal assessment. Students want to know / learn an English that is standard or general as the exams and tests assess this ‘standard’ language. However, i have worked in Northern Ireland for many years and there major variations in language/ accent 50 miles apart and the students want to know whether they should be learning ‘standard English’ or Northern Irish English – it also depends on whether they intend to stay here in the north or move elsewhere to other English speaking countries or use their English in other countries.

In Myanmar, several indigenous groups and ethnics are coexisting together, possessing various language varieties as well as languages. Burmese being the official language, some regional languages are mutually unintelligible. For instance, သူပုန် /tha-bone/ means “rebel (n)” whereas, in Rakhine, it means “soap”. This shows ‘Standard Burmese’ is a dialect, just as non-regional as ‘Standard English’.

I’m from the USA, and there’s a Louisiana creole language derived from French. There are words and grammar and spellings derived from French, but over generations, the mixing with other languages slowly made it mutually unintelligible from French itself.

The thought that ‘Standard English’ is a non-regional dialect rings true, I believe. It didn’t originate from one particular area, it’s made up of codified grammar and spellings, some of which even native speakers would find archaic in nature. English amongst native speakers constantly evolves with each new generation, technology, and the mixing of different cultures.

The popular linguistic phrase, ‘A language is a dialect with an army and navy’ seems appropriate here. I think that ‘Standard language’ is also a dialect that has been given more prestige and attention. Igbo, which is my L1, has more than 100 dialects. However, what is considered ‘Standard Igbo’ is a variety has been codified, used in education and other official settings, and used by all to promote mutual intelligibility.

In my experience, the term dialect is very often used when merely referring to a different accent. This is at least true when it comes to Swedes. We often refer to the word ‘dialect’ when we are asking people where they are from. In my opinion, the question is rather what accent they speak than what dialect they use. Unfortunately, in Sweden real dialects are slowly dying out. As we have such an easy access to sound and video of today there is not the same “need” for dialects. We tend to instead keep accents alive and the occasional regional word but on the whole it is fairly the same.

That is pretty much the case with dialect in Finland. Everybody knows ‘standard Finnish’ and that is used in the written media, but people speak either in more or less general spoken Finnish or in their own regional dialect, which is more clearly heard in for example eastern or south-western Finland than e.g. in the capital region.

I can also see similarities between Swedish, my native tongue, with what you describe about Standard Finnish.

I believe the same applies to the Malay language as well. Personally, depending on the region one resides, the individual will adopt the local dialect of the region. However, within linguistic education, the standard Malay is taught in schools to generalise its use to those who are unable to speak in specific dialects when travelling to other parts of the region.

The same could be applied to English. In educational settings, standard English is taught in schools. But as Malaysia is a multicultural country, much of what is spoken out of educational contexts has been adapted and changed according to the local context.

I cannot help but mention that many people, organisations, and even countries have benefited greatly from the idea of “THE LANGUAGE”. The English Language Learning industry is a multimillion one.

Couldn’t agree more. ‘Standardised English’ remains prominent in ELT because of its economic values. I do hope growing research in English as a Lingua and Multilingua Franca and Global Englishes can finally make different in more practical sense:)

I lived in the USA a long time ago and I was always told I sounded quite formal and serious. It was the standard British English I had been taught in Spain for many years. What we call “the norm” is a set of established rules that should be seen as the rudiments we need to communicate, but language is different: it evolves and depends on many factors that we aren’t usually aware of unless you become a teacher or you experience ir first-hand. However, the business in ELT continues to promote standard models and nowadays there is a pressing need for international certifications that still support it. The context is everywhere and everything at the same time. If you work with an international team where communication is more important than form, you don’t tend to focus on the latter unless it leads to enhanced communication. As regards a more social perspective, I strongly feel as a non-native speaker that there is an unconscious movement to facilitate communication. In other words, as long as there is communication we don’t really “care” about standard or non-standard usage of the language. In brief, it is speakers who make up the language regardless of their origin.

This is such a great point! I totally agree that the focus on rigid “standard” English is becoming increasingly irrelevant, especially in international settings. Your experience of being perceived as overly formal in the US really highlights that. The push for international certifications that prioritize prescriptive grammar often feels outdated. The reality is, effective communication trumps grammatical perfection. And I think you’re right – there is an unconscious movement towards prioritising understanding above all else. It’s the speakers who shape the language, not the rulebooks! Thanks for sharing your perspective!

Hi there:

I am from Colombia, and of course we have regional dialects that differ from one another in such aspects as grammar, accent, pronunciation, and even vocabulary. For instance, some days ago I was discussing with my students in class the differences in UK and US English considering words like “trainers” VS “sneakers” or “jumper” VS “sweater”. They were surprised to see how learning English also requires them to learn how to use vocabulary in different variations of the same language.

Then, one student said that learning all that was such a difficult endeavor, and that she was better off only learning the basics, like in Spanish. Then I asked them all to consider the word “perico”, which in Colombia can have up to 5 different meanings. In the capital city, the word means “coffee with milk”, while in the Andina region, the word means “scrambled eggs with onion and tomato”. Also, in most of the country, the word is also related to a bird, a psychoactive substance, as well as a tool.

That said, I consider that the idea of “Standard English” is in fact a non-regional accent. It is an idea of a normative conception of the language, one which is appropriate for scenarios like politics, technology, or the media industry. However, in everyday communication, English speakers bring with them different realities which are based on their places of origin, life experiences, as well as persona orientations towards the language.

It is interesting that here mentions that Mandarin is imposed by China’s government, mostly criticised. But, Enough was also imposed in the past and still imposes. The difference is that today it imposes in soft power way.

First I thought it’s rather easy to define the difference between a language and a dialect. In Finland we have two national languages, Finnish and Swedish: Finnish-speaking people don’t understand Swedish without teaching, but they do understand people speaking a different Finnish dialect. In the big picture, I mean. There are, of course, Finnish words that the Swedish-speaking people use (in Finland), and vice versa. And then there are also words that are only used in one dialect, but not in another. Or words may have different meanings in different dialects.

But then there are languages like Swedish, Norwegian and Danish that have more in common with each other than with Finnish, for example. When you know Swedish, you are able to understand at least some words in Norwegian and Danish as well. So, there probably cannot be one “true” definition of a language or dialect that we all could agree on.

According to Cambridge Dictionary, a dialect is “a form of a language that people speak in a particular part of a country, containing some different words and grammar”. As a Swede, coming from the southern parts of the country, the region of Scania, I speak a very specific dialect of Swedish. Our dialect is heavily influenced by the Danish language (words mostly), however, we still speak Swedish. The regional dialect of Scania uses “heavy” diphthongs, so instead of saying “Å” or “E” vowels in Standard Swedish, we use the diphthongs “AO”, “AI” and “ÅI” which changes the pronunciation of the words a bit.

I feel that the discussion about standardized languages (like Standard English and Standard Swedish) and if they are non-regional dialects is valid, I think they are no more right than any other dialect, and who actually uses it daily? I mean speak it.

I agree with the linguistic claim that ‘Standard English’ is (just) a non-regional dialect or that is made up this way by authorities to have a common idea of language as a society . This way educaiton is globalized through ‘Standart English. Altough I dont claim that it is true or the way that is to handle the differences between cultures , dialects and languages. But I think this claim makes it easier for teachers to prepare activities in classes as they set up a view off ‘Standart English’.

I am from Colombia, and I have evidenced regional dialects which have their own particularities such as accent, vocabulary and even pronunciation. Nonetheless, it is uncommon to use the word ‘dialects’ to refer to indigenous languages, and I think it is intertwined with the fact some indigenous languages do not have a dependency or origin in the Spanish language, they have their own grammar and vocabulary, which are directly associated with their worldview.

On the other hand, I agree with the thought that ‘Standard English’ is a non-regional dialect. It wasn’t originated in a specific area; it has origins involving grammar, spelling and mainly correctness, as well as ‘Standard English’ has an idea of a normative perception of the language, which is appropriate for fields such as politics, business, economics and even educational aspects. However, in everyday communication, English speakers and English learners entail with them a variety of realities which are related to their life experiences, and including the resources used throughout language learning.

British society was stratified in the late 19th and early 20th century. George Bernard Shaw in the preface to Pygmalion remarked that “it is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman hate or despise him”.

Nowadays, I believe, the way you speak also indicates your social status and background. Despite regional variations (dialects) that are numerous across the UK as well as other countries, we also need to consider social identities that shine through our language.

In the times when English has become a lingua franca, the world (except native speakers) is celebrating Globish. Thus, the notion of Standard English is quite vague and no longer relevant in the global

In the UK there are many people who would hold the view that standard English is the more upper-class form of English, which I would typically associate with varieties of English features such as high register and jargon within their speech, on the other hand, there is non-standard English, which is more colloquial language, users who use non-standard English who I associate with this variety of English are those from the lower class such as those from Council house estate areas.

I feel that standard is almost like a dialect in its on way, while non-standard English users’ repertoires are more limited to non-codified, simplistic words which don’t appear in dictionaries, use more low register, and almost never omit Jargon, or specialist terminology, but in comparison to standard English users, the two varieties are both mututally intelligble but different in some ways.

I believe that “Standard English” can be valuable in formal contexts like politics and lectures. However, in everyday language, no single “Standard English” exists, as various dialects embody unique cultural aspects. The notion of “standard” is often shaped by factors such as power and prestige, rather than reflecting a universal norm.

I believe that with English being a plurilithic language, trying to teach and set an idealised way of speaking such as what is referred to as ‘Standard English’ is unattainable, especially with the rise of English being used as a Lingua Franca – a means of communication for different countries and languages, and it being used in so many different ways and for many different reasons.

It is damaging for people to hold a language/ languages to these so called ‘standards’ as it doesn’t leave any room for the regional dialects and language varieties (which are a huge part of people’s identities) to be acknowledged or accepted.

Despite this, I can agree that there does needs to be a certain level of grammatical structure in which a basic standard is set, so learners can comprehend the rules of English for example, but to generalise there isn’t a true reason as to why, regional accents or the so called ‘errors’ cannot be accepted as apart of the English Language, rather than them being accepted and celebrated, especially with the influence of technology which is increasing the pace in which language is being consumed.

I think the distinction between a dialect and a separate language is almost impossible to define. The fact that indigenous languages and minority languages are often ‘relegated’ to dialects implies a dismissive approach that sees dialects perhaps as aberrations from the standard.

The concept of standard english being a non-regional dialect makes sense, as it seems to exist more as an ideal than as a way anyone naturally speaks.

In english a dialect refers to a specific areas way of communicating, usually through different use of colloquialisms which is rather different from Mexico and how they see indigenous as different dialects, this opinion was likely formed due to colonisation and shows a more biased opinion towards their language. Similarly, ‘standard English’ would be considered something someone of a higher class would be expected to be able to speak due to more access to better education, this also shows biased opinions in language.

There are several regional dialects in Lithuania in addition to “standard Lithuanian” that is used and understood everywhere. These dialects are treated more like cultural and linguistic phenomena rather than functional languages – it is generally agreed that none of them could possibly replace the standard one. I don’t think that people who know and use them feel in any way inferior to the rest of the population or would like their dialects to gain more prominence and/or compete with the standard.

P.S. I’m totally ok with the thought that Standard English is just one of the dialects that got its place in the hierarchy due to various random reasons that have nothing to do with its linguistic superiority.

yes, true.

I strongly agree with linguists’ view toward Standard English. They are wise enough to put Standard English as a part of dialects that do not represent dialects as lacking for users. It is terrible seeing how those folk beliefs put dialects in the same line with errors, in which they assume users with particular dialects are not worth enough to practically use the language.

In my country, English is still viewed by the standardized system. Someone who speaks English with particular dialects seemed to be not proficient in using the language. Even though they are teachers or lecturers, they need to speak like natives to be admitted to being educated.

This discussion highlights the inherent hierarchies that exist in language. The term “dialect” itself is often loaded with negative connotations, suggesting a less sophisticated or less valuable form of communication. It’s important to recognize that all languages and dialects have their own internal logic and complexity, and that the “value” assigned to them is largely determined by social and political factors, not by any inherent linguistic qualities.

Dialects are as much part of English as standard English, so I believe that it is correct to place standard English as just another dialect. Great Britian colonised many parts of the world and brought their language there. One example would be India, where most people speak English, some even as one of their first languages. They do have an Indian dialect but that doesn’t make them any less proficient in English. I believe that putting dialect next to errors is very disrespectful because it makes it look like someone with a dialect doesn’t not have the vocabulary or grammar to speak good English just because their dialect isn’t the social norm.

We were trained as English teachers and taught Received Pronunciation (RP). Our teachers had North American and British accents. I clarify this because I realize that when we teach in schools, we use an English constructed with all these regional and usage differences.

With this brief introduction, I want to emphasize that we, as teachers, contribute to globalizing the English our students will use to communicate outside the classroom. And of course, there is a hybridization with the influence and contribution of the media too.

In Indonesia, a similar situation exists. Many regional languages, such as Javanese, Sundanese, Batak, Bugis, and Minangkabau are often called “dialects”, even though they are actually independent languages with their own grammar and history. The use of the term “dialect” is often influenced by social and political factors that place Bahasa Indonesia in a higher position.

Regarding the claim that Standard English is just a non-regional dialect, I agree linguistically. It is simply one variety that gained prestige through history, education, and power,not because it is structurally superior. All English dialects are equally valid from a linguistic perspective.

Overall, the distinction between “language” and “dialect” is shaped more by politics and social attitudes than by linguistic facts.

about “Standart English ” being just a non regional dialect,-honestly that make sense. There is nothing special or magically “correct” about standart English. Its just the variety that got the most power and ended up being used in schools,media and exams. At the end of the day, it’s still just one dialect among many others, only with higher status.

In Ukraine, the word dialect is often used to describe ways of speaking that are seen as less prestigious than the standard language. For example, regional varieties or mixed forms such as surzhyk are sometimes called dialects, even though they are widely used and follow clear patterns. As in many other countries, these labels often reflect social and political attitudes rather than purely linguistic differences.

In Indonesia, a comparable trend is observed, with numerous individuals using the term ‘regional languages’ (bahasa daerah) to describe languages like Javanese or Sundanese. These languages are occasionally viewed as less important than Indonesian, the country’s official language, even though they have intricate and self-contained linguistic systems. Concerning ‘Standard English,’ I share the viewpoint of linguists who consider it a dialect without any regional ties; fundamentally, it is a version of the language that acquired status because of social and political forces, not because it was inherently better in terms of language. By understanding it as a dialect, we recognize that it represents just one manner of speaking—originating historically in the East Midlands and London—that was formalized for official communication across different areas

I am from Germany and there are several dialects such as Bayerisch, Sächsisch, Niederdeutsch, Fränkisch, Plattdeutsch. In fact it is hard to distinguish dialects from regional languages. And I agree that in the ‘folk view’ dialects are seen as something inferior. Whereas the the usage of the term ‘regional language’ shows a revaluation of the diversity within the German language.

Standard English to me means as much as Hochdeutsch in German. It is a non-regional and dialect free version of a language which is often advised to be learnd as a language. Unfortunately most people do speak some kind of dialect so if you learn a standard language native speakers are able to understand you but it doesn`t mean that a learner of a language is able to understand native speakers unless they speak their standard version of their mother tongue. Words can differ in pronunciation as well as meaning depending on what region you come from.